Before Genomics, Citrus Breeding was a Study in Patience

by Robert K. Soost

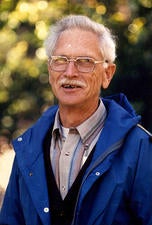

Robert K. Soost, Professor Emeritus of Genetics, was on the faculty for 37 years until his retirement in 1986. He served as chairman of the Department of Plant Sciences from 1968 to 1975. His research included a focus on nuclear embryony and the cytology of citrus, and he was considered a world authority on citrus genetics and breeding, consulting in other countries, training visiting scientists from foreign nations, and speaking at international conferences. He was elected a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Society for Horticultural Science, and he served as associate editor of the Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science for nine years. He wrote this article in February 2001. Dr. Soost passed away in March 2009.

It was quite an honor when University leaders decided to plant an Oroblanco grapefruit tree at the Citrus Experiment Station's 75th anniversary commemoration ceremony in 1982.

No doubt Chancellor Tómas Rivera was signaling the growth and evolution of the University and its mission, but I was marking an additional and personal achievement, the fruition of 25 years of research with my colleague, James W. Cameron.

I had arrived at Riverside and the Department of Plant Breeding in 1949. Although I also researched tomato crops and Jim worked on corn, we were both hired — Jim a few years earlier than I — to share responsibilities for the important citrus breeding program developed by Howard B. Frost.

A legend in citrus genetics, Dr. Frost was one of the first scientists to join Riverside's Citrus Experiment Station (which would evolve into UCR) when it opened in 1913 [sic]. Dr. Frost laid the foundation for the modern understanding of the genetic structure of citrus, being among the first to describe the number of chromosomes in a normal citrus fruit, for example.

He also bred thousands of seedlings during his 30-year career and gathered a number of different citrus types to use for breeding purposes. Decades later, I could point to several commercial citrus varieties grown in California as directly related to the research of Dr. Frost.

Citrus breeding had begun in earnest in the United States in the late 1800s, yet UCR was one of the few places in the country in the 1940s, as well as today, to have an organized citrus breeding program.

Fruit tree breeding, especially using classical breeding methods, is a difficult task. Researchers can count on a process of 10 to 15 years from the first step, in which parents with desirable traits are identified and crossed, until the next-to-the last step, when fruit is produced from the trees planted using the most promising seedlings. Then follows another 4 to 5 years of extensive field-testing to ensure that a new variety poses no risks and will continue to thrive and fruit.

Time is not the only obstacle. Our accomplishments in fruit breeding have been limited by the technology and the knowledge available. One would have liked to do many things to improve citrus fruit for growers and consumers, such as breed navels that ripened in a different season or developed seedless varieties, but neither the knowledge nor tools existed to create hybrids with precision.

Relying on classical breeding methods, we transferred the entire genetic code from one tree to another — and we necessarily took mixed results as the best outcome. Over the decades of our collaborations, Jim and I succeeded in developing several new varieties, including Encore and Pixie mandarins and the patented varieties Melogold and Oroblanco hybrid grapefruits, which are still used commercially today.

Each offered something interesting and advantageous - less acidity, new colors of flesh - but it wasn't as if we were able to take the best of both fruit trees and discard the less desirable characteristics.

The public never questioned what we were doing, although we were just as surely prodding Mother Nature as geneticists are today. Maybe consumers were unconcerned because we were practicing what seemed a "natural" breeding process that did not require the probing or manipulation of plants at the molecular level. Or maybe it was because the public had few qualms about scientists exchanging genetic materials among plants in the same species or genus.

However, as different as public opinion was compared to today, the viewpoint of scientists has not changed much. Plant geneticists were aware decades ago of the need to guard against "genetic pollution," the unintentional transfer of genes to wild plant populations.

We also worried about the safety of the vegetables and fruits that resulted from crosses since the slim possibility existed that the genetic cocktail created by hybridizations would lead to the development of toxins or allergens. Even in the 1960s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had safety guidelines in place. Known as "GRAS," Generally Regarded As Safe, the policy outlined the procedures to use and the tests to be conducted to protect the safety of crop populations and food products.

Now that geneticists and breeders have advanced in their understanding and are able to employ more sophisticated technology so that they can target individual proteins that regulate fruit and tree characteristics, the questions for scientists remain the same. What has shifted is the scope and number of questions.

Certainly the potential exists for different types of problems if you are introducing genes from bacteria rather than genes from the same species of plant. However, the same extensive field and lab tests will be conducted and the risk is now, as it was in the past, manageable. The technology is so promising that it seems very clear to me that it must be further explored.

About a year ago, as the University celebrated the end of "100 years of citrus research," it made the commercial release of the sweet, seedless Gold Nugget tangerine. Professor Mikeal Roose had completed the evaluations and field tests in a process that Jim and I had started in 1958 when we screened seedling populations of the cross of Wilking and Kincy varieties made by Dr. Frost.

Today Professor Roose is immersed in biotechnology, seeking to transfer only single genes rather the entire chromosomal structure. I think the future looks bright since the day might come when breeders can develop fruit varieties to order, so to speak, adding just the precise amount of the characteristic that is wanted, but nothing else.

Years of field tests with trees growing under various conditions and in different environments will always be a necessity, but we are nearing the day when citrus breeders can say that their efforts will bear fruit in less than a decade. The more predictable and less time- and labor-intensive breeding becomes, the more likely consumers and growers are to benefit from new varieties that result from the efforts of thriving breeding programs.